In the months after her husband’s unexpected death, Molly Goodfellow found comfort in quiet moments.

Losing Bobby was an earthquake. At 39, he had cemented himself as a South Baltimore community staple; a generous colleague at the Maryland Shock Trauma Center; and a beloved father to their young son, Henry.

A self-described introvert with a career at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, Molly has been left to pick up the pieces. So when the messages from real estate agents and investors started trickling in, a renewed sense of anger came with them.

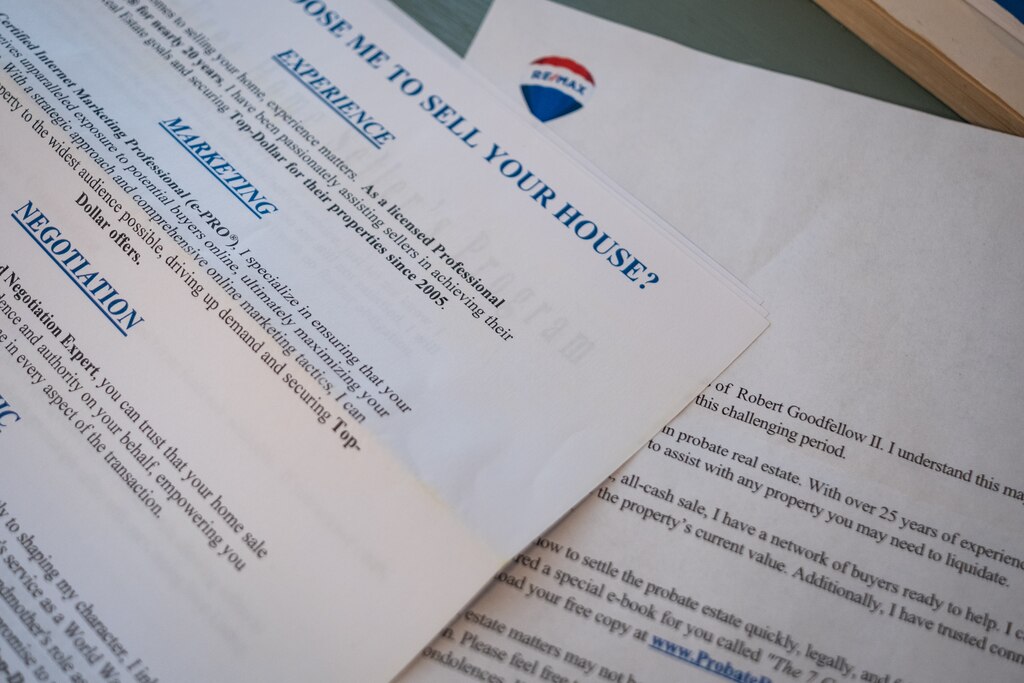

Molly has received multiple inquiries from people in pursuit of her house, some mentioning Bobby by name and others not. They all seemingly want to know: In light of his death, is she open to selling their shared dream?

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Housing professionals have myriad ways of finding clients: Handing out business cards, sharing flyers and posting on social media are all part of most modern operations.

While licensed real estate agents typically aim to abide by a code of ethics, though, there’s nothing in the rulebook that specifies how to behave toward prospective clients, particularly those going through emotional or financial hardship.

Seeking answers hidden in her husband’s medical records, Molly thinks the agents and investors found her after she opened an estate with the Maryland Register of Wills this past April.

The unsolicited messages — sent via text and by mail, some more than once — have only caused more harm.

“They’re using public information to find people who they might be able to manipulate into making a decision,” she said. “It brings up a lot of the anxieties and feelings of panic that I don’t need.”

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Molly is still in the Goodfellows’ home — a three-story brick rowhouse in Ridgely’s Delight, the compact community nestled in a curve of Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard and bounded by Pratt, Russell and Greene streets. It faces the back side of Camden Yards and is within walking distance of work, day care and a playground. In a tight housing market with limited inventory, it’s no surprise that it has agents’ attention.

Molly and Henry, 4, have their life tucked into the house’s nooks and crannies: toys; artwork; photos of Bobby, young and smiling. In one room, foster kittens are awaiting their next homes. In another, Henry shows off his lofted bed and the family’s cat, Momo, napping peacefully there.

The Goodfellows bought the place in 2017, the same year Molly earned her doctorate in behavioral neuroscience and went to work at the university. They renovated the 1920s-era end unit and found friends nearby. At one point, Bobby led the neighborhood association.

Molly isn’t interested in selling. For one, after Bobby died, neighbors “rallied” around her and Henry, showing up at his tee-ball games, stopping by for dinner and watching him when she needs a hand.

“They just keep me company and make me feel less alone,” she said. “I don’t want to leave those people.”

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Maryland real estate agents are expected to abide by national ethics standards. Cheryl Abrams Davis, president of Maryland REALTORS and manager at RE/MAX United Real Estate, said while she wouldn’t personally attempt to reach prospective clients who just experienced a loss, she thinks some homeowners may want the help.

Some may not be able to afford keeping up a mortgage by themselves, she said, and might benefit from consulting a professional. Still, she said, real estate professionals should trust homeowners to get in touch when they’re ready.

“Sometimes,” she acknowledged, “it can take years.”

Some seasoned professionals said they’ve found other ways of doing business that don’t require invading people’s private lives.

June Piper-Brandon, a real estate agent who works in Maryland and Pennsylvania, said her client network keeps her plenty busy. One family, for example, has produced 12 separate referrals.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Piper-Brandon, herself a widow, said she finds fault with the “ambulance chasers” who exploit the vulnerable. When her husband died, house-hungry professionals bombarded her, too. The experience reinforced the value of using empathy to guide business dealings.

“People will remember, long after the transaction is over, how you made them feel,” she said.

A Maryland housing professional since 2003, Piper-Brandon takes on mentees and sits on a number of committees and boards in the industry. She recommends other agents be considerate, respectful, kind — and never pushy.

“There’s a reason we’re considered only marginally better than used car salesmen,” she said. “Don’t be the used car salesman.”

With every company abiding by different standards, Piper-Brandon said she sees a need for more training for agents before they go out independently — and more frank conversations about the pitfalls of the job.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

In a way, Molly has the same hope.

Though speaking out goes against her nature, she’s sharing her experience publicly to try to change how housing professionals govern themselves in dealing with grieving prospects.

She thinks Bobby, a natural “rabble-rouser,” would have said something, too. This was his home. He wouldn’t have let it go.

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.