Conversations among the Dali’s two Maryland-based pilots and its foreign crew members portray an unremarkable beginning to the container ship’s departure from Baltimore last year.

The senior pilot had stepped on a staple at home, he told the others. The Dali’s voyage to Sri Lanka would take one week longer than usual to avoid piracy in the Red Sea, the captain said. The apprentice pilot requested a little bit of sugar with his coffee.

But, in a recently released transcript of audio from the ship’s command center, one quick exchange stands out as an eerie omen:

“Captain, everything’s working?” the ship’s senior pilot asked at 12:16 a.m. March 26, 2024.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

“Yeah, everything is in order,” came the reply.

The vessel had experienced two blackouts 10 hours earlier. Soon it would have two more — precipitating the catastrophic collapse of the Francis Scott Key Bridge. Six construction workers who had been filling potholes on the span were killed, and building a new bridge is expected to cost almost $2 billion.

Read More

At 1:25 a.m., alarms interrupted basic navigational talk and casual chatter. The 100,000-ton vessel, headed toward an essential Key Bridge support, had suddenly lost power.

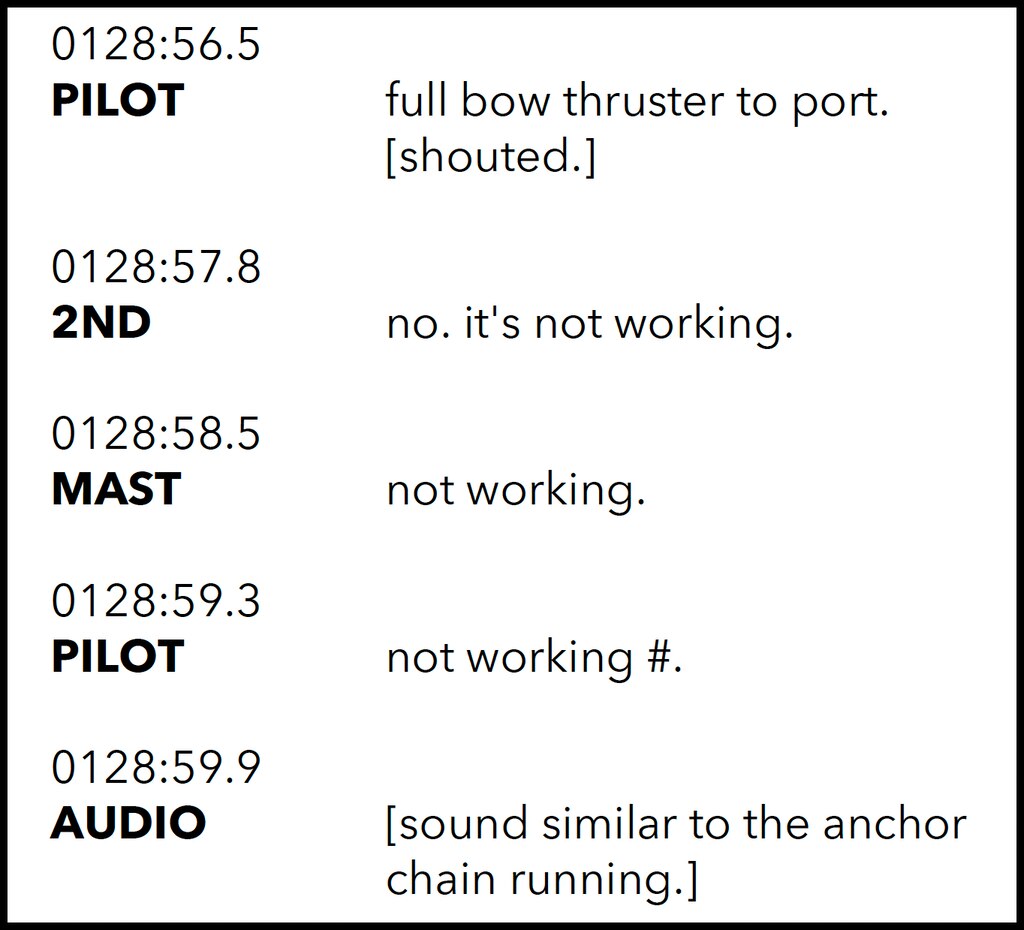

During four frantic minutes, the pilots shouted futile, last-gasp directives as light music continued to play. They asked a dispatcher to close the bridge to traffic. Handsets slammed. The senior pilot shouted in vain for emergency use of a bow thruster, a device that helps ships maneuver laterally when docking.

“No. It’s not working,” the second officer replied. Those were among the final words uttered before the collision.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

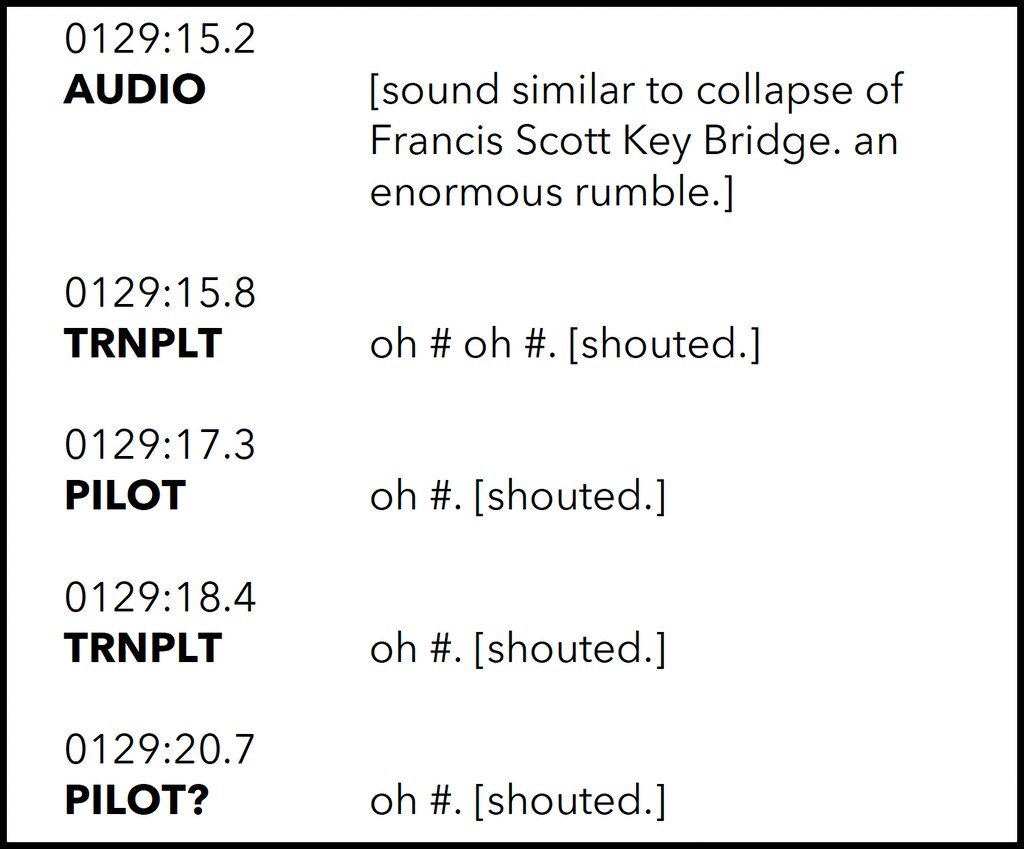

“Holy [expletive]. Holy [expletive]. Holy [expletive],” the apprentice pilot, shadowing the senior pilot, said at 1:29 a.m., seconds after the collapse.

The command center transcript, which has not previously been reported, was made public in April by the National Transportation Safety Board, which is investigating the tragedy.

Other new NTSB materials include transcripts of interviews with crew members and the Dali’s former chief engineer, whom investigators queried about the frequency of large vessel blackouts.

The captain’s assurance to the local pilots that the Dali was in working condition supports an allegation in the federal government’s lawsuit against the Singaporean owner and operator of the vessel, Grace Ocean Private Limited and Synergy Marine Pte. Ltd, that the pilots were not fully informed of the ship’s state by the crew.

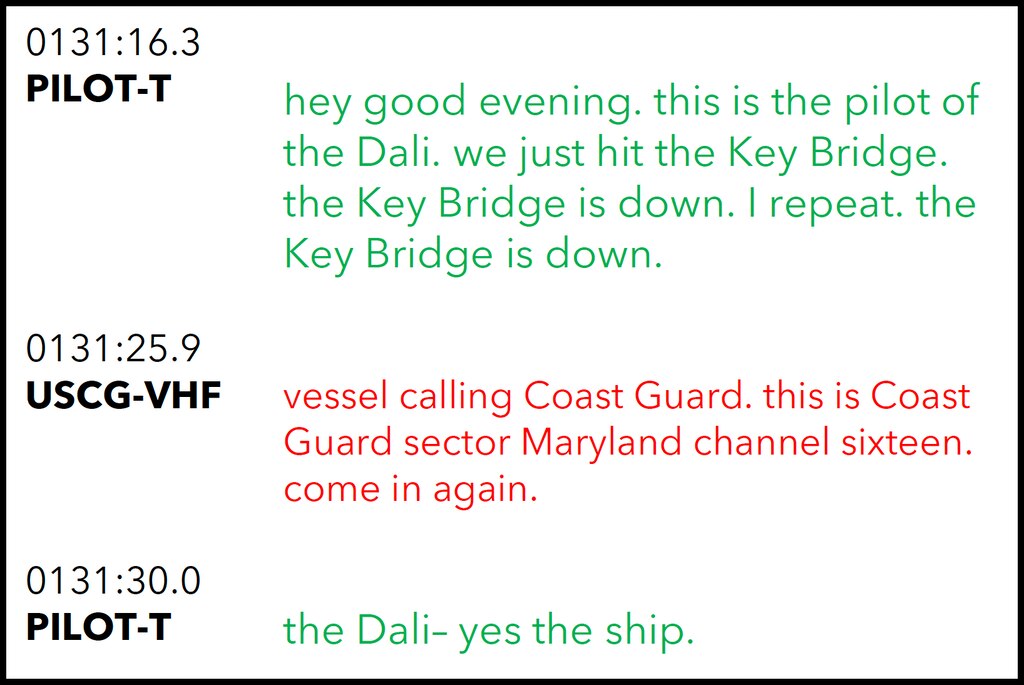

Seventeen seconds after the collision, the apprentice pilot likely became the first person to shout the words that Baltimore and the country would soon awaken to: “The Key Bridge is down.”

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

He later offered a “quick nervous laugh,” per the transcript, and said, “Ohhh dude hooollllyyy—” as the senior pilot added: “Now this is a problem.”

They noted they would each need to take a drug test — later testing negative, per the NTSB — before reflecting upon what had caused the tragedy. The ship wasn’t “going crazy,” the pilots said to each other, and they had had everything “under control.”

“Uh, what did we do wrong?” the senior pilot asked.

Expert local pilots are required by state law to guide large vessels through Maryland waters. In this case, a pilot-in-training accompanied an experienced colleague on the transit south.

The NTSB’s transcript did not identify the pilots. The Association of Maryland Pilots has not named them and declined to comment.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Two tugboats escorted the Dali out of Baltimore, as is typical, before the pilots told the boats they could detach.

“I like my chances if you want to take off,” the pilot radioed to the Bridget McAllister boat at 1:06 a.m.

“Alright,” the tugboat captain replied. “All done here. Safe trip.”

After the Dali lost power, the senior pilot radioed for the tugboats to return, asking one to “hammer down” and swiftly return. At that point, though, the tugboats were miles away and incapable of assisting.

Elsewhere on the ship, Alan Babu, the ship’s second officer, heard the blackout alarms and proceeded up a staircase toward the command center. Moments later, he “saw the bridge collapsing,” he said.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

“I didn’t know whether I should go forward because all (the debris) will be falling in front of me,” Babu said, according to a transcript of his interview with investigators.

Babu and helmsman Maragasseri Rajan were separately interviewed, with their attorneys present, on the Dali in the days after the incident, while the ship’s bow sat underneath a huge piece of the bridge.

Rajan told investigators that he did not notice any problems with the Dali the day before it departed Baltimore, calling it a “very nice vessel,” but Babu recalled that the ship had lost and then regained power that afternoon — prompting him to wake from a nap.

That power loss was emphasized in a lawsuit from the federal government, which described the ship’s electrical system as “jury-rigged.”

Babu wondered if swifter action by those aboard could have allowed the anchor to be dropped earlier and prevented the collision, but Rajan demurred when asked if anything could have prevented it.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

“No, no, no,” he told investigators. “No opinion.”

The NTSB also conducted a two-hour video interview with the former chief engineer of the Dali, Dhurai Balaji, to understand the ship’s electrical system and how common similar blackouts are. Balaji estimated that, in his decade of experience on large vessels, he’d seen blackouts four or five times.

Investigators tried to ascertain the qualifications of the Dali’s chief engineer at the time of the collapse; Balaji had previously spent a day with that engineer, handing off his duties, and said his replacement had prior knowledge of these types of ships.

“I didn’t have any difficulty in handing over,” he said.

At the crux of the NTSB’s investigation is how to prevent future accidents. But litigious parties will be keeping a keen eye on the examination.

Amid federal investigations, about a dozen members of the Dali crew remain in Baltimore, according to Barbara Shipley, the International Transport Workers’ Federation’s mid-Atlantic representative.

The Department of Justice, which was investigating the case as of last year, has requested crew members remain in Baltimore. Department spokesperson Kevin Nash declined to comment.

Maryland officials have pointed the finger squarely at Synergy Marine and Grace Ocean for failing to remedy flaws in the Dali, prompting the disaster. The Justice Department argued as much, too, describing the vessel as “abjectly unseaworthy.”

Both have sued the Dali’s owner and operator, as have attorneys for the victims’ families and dozens of others. But another target might soon emerge: Maryland.

More than 20 people and businesses have expressed to the state that they intend to sue Maryland for failure to keep the bridge safe, according to The Washington Post. A spokesperson for Maryland’s attorney general declined to comment.

The Dali is long gone. It was escorted last year to Norfolk, Virginia, where much of its damaged cargo was discarded (275 tons of soybeans, for example, went to a Virginia landfill), then sailed to China for repairs and returned to service this year.

Demolition of the Key Bridge’s remaining structures, still in the Patapsco River, had been scheduled for last year but is now projected for this summer, said Bradley Tanner, a spokesperson for the Maryland Transportation Authority. Construction is then expected to begin later this year.

The investigation and its ramifications march on.

“I hope like this investigation goes in the best possible way,” Babu, the Dali’s second officer, said, “and this doesn’t happen ever again in the shipping industry.”

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.