Brian Matusz appeared to have it all.

The Orioles went into the 2014 All Star break with the division lead, their best start in 17 years. Even the most pessimistic Baltimoreans were having World Series dreams. Brian had pitched in 40 games and had made a name for himself as rival Red Sox slugger David Ortiz’s Kryptonite.

He was young, handsome and very wealthy. With a few days off, he could’ve jetted anywhere for his midseason break. Instead, Brian went home to the beige and terra-cotta sprawl of the Valley of the Sun. Phoenix is a most uninviting place in mid-July; the average daily high is 105 degrees. But Brian wasn’t looking for a tropical ocean breeze.

He found what he sought from his best friend, Taylor Palmer, whom Brian had known since elementary school. Taylor texted Brian to let him know he had Percocet, a prescription opioid. Come over right away, Taylor remembers Brian responding.

Taylor said he and Brian had dabbled with pills in the past. Weekends during the offseason or stretches when Brian was injured meant posting up on the couch for eight to 10 hours, smoking weed and ordering takeout. Taylor assumed this would be like those times. Brian was in town for only three days and probably had other things to do.

Taylor was wrong. Brian, it seemed, was intent on doing Percocet for three days straight, until he’d disassociated. “Zombied out,” Taylor described it.

“I remember thinking, ‘If he’s like this with me right now, he must be doing this during the season,’” Taylor said. The alarm bells started going off: “You can’t fuck around with this drug and be a professional athlete.”

The next decade would be a procession of losses — his marriage, his career, his friends — until there was nothing left for Brian Matusz to lose but himself. On Jan. 6, Brian died alone in his home in Phoenix. Police said it was an apparent overdose. He was 37.

Friends and former teammates would later say they could tell something was wrong — losing baseball had left Brian adrift — but they didn’t know to what degree. Others did.

“A year ago, I knew this was going to happen,” Taylor said. “Five years ago, I knew this was going to happen.”

Professional athletes’ beginnings are so cliché. There are fawning coaches, glowing write-ups in the local paper and performances so dominant their retelling takes on a mythic quality.

Death inflates all of that. And it can offer hindsight.

By the time Brian was a senior in high school, in 2005, it was all but guaranteed he was going to be a Major League Baseball player. Scouts, sometimes 20 at a time, flocked to St. Mary’s Catholic games to watch this tall left-handed pitcher with a nasty curveball. The only real question was whether he would go to college or straight to the pros. Brian told a reporter it depended on the money. It would have to be a “good amount” to skip the college experience.

Brian knew baseball just as well, if not better, than his high school coaches. Keith Merkel, former head coach of St. Mary’s Catholic, said he let Brian call his own pitches as a junior, a privilege usually reserved for seniors. Brian sometimes could spot something from the opposing pitcher, a tell maybe, that his coaches couldn’t.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Danny Rodriguez has coached high school baseball in Phoenix for 38 years. He’s had three players, including Brian, go on to the major leagues. Andre Ethier, the two-time All-Star outfielder for the Los Angeles Dodgers, and Nick Evans, a journeyman who bounced around with a few different teams, were the others.

Brian was the best, Danny said. Unlike other burgeoning stars, he never complained and always did what was asked of him. He was a dream to coach.

“An all-American kid,” Danny said. “Somebody I would have wanted my daughter to be with.”

In March of Brian’s senior year, the Arizona Republic published a piece that said the only thing out of place in his life was his shaggy hair. It said he didn’t even have a pet peeve. “Brian Matusz can’t be this refined,” the story’s first line read. “Does the local kid, who, by the way, struck out 16 batters in a seven-inning game earlier this week, have any flaws?”

“I’m not neat off the field,” he told the newspaper. “But I am on the mound.”

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

One game in particular showcased the depth of Brian’s talent.

St. Mary’s played top-seeded Salpointe Catholic in Tucson in the 2005 playoffs. Salpointe was laden with talent, with maybe eight Division I-caliber players on that roster, remembered Jim Schilling, a St. Mary’s assistant coach.

The scorebook is lost to time, but Jim remembers Brian striking out 12, maybe 13 batters. He also hit a home run and two doubles, singlehandedly lifting St. Mary’s to a 4-3 win and ending Salpointe’s season. The next year, the Arizona Interscholastic Association changed the format of the baseball playoffs from single to double elimination, ensuring no one player could ruin another team’s season.

One of the things his coaches and the scouts liked most about Brian was his work ethic. Teenagers were not usually this disciplined. People credited Brian’s upbringing, specifically his father. Mike Matusz understands discipline and knows what it takes to be good at something. He ran track at Purdue. He made his career in construction. But, for his two sons, baseball was their common language. Brian and his brother could spend all day at the ballfields, and Mike would be there with them.

Expectations were high. Mike was strict and hard-driving, an ever-present figure around Brian’s baseball teams from Little League through high school.

“I think his dad was a little bit tougher than anyone thought,” Danny said. The Matuszes declined to be interviewed.

Mike’s strategy worked. Brian was drafted in the fourth round in high school, but the money wasn’t right, so he took a scholarship to the University of San Diego. He would go on to be named the West Coast Conference Pitcher of the Year and a first-team All-American his junior year, when he led the nation in strikeouts.

The Orioles picked him fourth overall in the 2008 draft, and this time, with his $3.2 million signing bonus, the money was right. Mired in mediocrity for the past decade, the Orioles were building a corps of young pitchers and Brian was expected to play a key role. He made his major league debut at age 22. In 2010, his first full major league season, he finished fifth in American League Rookie of the Year voting.

To this point, Brian’s life had gone exactly as it was supposed to. The all-American kid looked like he might become an All-Star.

But in 2011 he strained a muscle in his chest and pitched in just 12 games, going 1-9 with a 10.69 ERA. It was one of the worst statistical seasons for a starting pitcher ever. By 2012, the Orioles had decided to make Brian a relief pitcher.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

He never got over it.

Being a reliever in the majors is a sort of paradox. They are some of the best pitchers on the planet, but they play for just a handful of outs and, unless you’re the closer, there’s little glory.

The old baseball adage that all relief pitchers are failed starters might be hard and not exactly true, but the move didn’t sit well with Brian.

“He looked at the bullpen as a demotion,” Buck Showalter, the beloved former Orioles manager, said.

It’s not like Brian was an anonymous reliever. He pitched in seven postseason games and became a folk hero for being the only guy who was guaranteed to handle Ortiz, the hated Red Sox star who hit 541 home runs in his career. None came against Brian. In 30 plate appearances opposite Brian, Ortiz managed just four hits. The Mid-Atlantic Sports Network, the Orioles’ broadcast network, even turned Brian’s success against Ortiz into a commercial.

“He never didn’t compete or show up for his teammates. He was never a problem,” Showalter said. “He never let it play out on the field or his interaction in the locker room, but in private moments I would create an avenue for him to share what he was really feeling, and he did.”

What Brian felt was discontent. He wanted his old job back. The routine. Knowing you’re the guy every five days.

Some of his teammates said they noticed his personality dim but nothing that caused any real concern. The baseball season is long and repetitive, and they assumed that was weighing on him.

Professional baseball did not include tests for opioids in the random drug screens of players during this period. It’s unclear if Brian’s teammates or manager knew Brian was using — none of them would talk about it on the record.

"He looked at the bullpen as a demotion."— Buck Showalter, former Orioles manager

At the same time, Brian had burnished his reputation as a beloved community figure. He worked with Casey Cares Foundation, which helps critically ill children and their families. In 2015 the Orioles nominated him for the Roberto Clemente Award, which goes to a player with “extraordinary character, community involvement, philanthropy and positive contributions.”

In 2016, Brian missed all of spring training with a reported back injury and didn’t make his season debut until the end of April. He struggled.

The Orioles traded him in late May, adding a draft pick to convince Atlanta to take him. Orioles fans celebrated his departure despite getting two middling prospects. The Braves never had real plans for Brian and released him.

He signed a minor league deal with the Chicago Cubs a few weeks later and made three appearances for their Triple-A affiliate.

Then Brian got his break. The Cubs needed a starter for a nationally televised game on a Sunday night in July. It was Wrigley Field, one of baseball’s great cathedrals, on ESPN, the pinnacle of prime time.

In what Cubs fans now refer to as “the Matusz game,” Brian allowed six runs in three innings, all by way of two-run home runs. Fans remember the game because the Cubs came back, won in extra innings and went on that season to win the World Series, breaking a centurylong curse.

But Brian was there for only one night. Chicago cut him the next day.

Brian began dating the woman who would become his wife in January 2015 after reaching out to her on Facebook a few months earlier. She’d also gone to St. Mary’s but was a year behind him. And she’d been a cheerleader for the Arizona Cardinals — Brian and his brother loved the Cardinals.

They spent Valentine’s Day together, and by the time the 2015 season had started Brian was flying her to Baltimore for long weekends. Eventually he asked her to quit work and live with him.

The woman signed a nondisclosure as part of the couple’s prenuptial agreement. Neither she nor her family responded to requests for an interview; her name is being withheld because she is the victim of domestic violence. But recordings of court proceedings, police records and an application for a protective order portray a volatile relationship. One day there would be lavish gifts; another, violent outbursts and allegations of drug use.

Brian was “manic,” the woman said in court once, adding that he might go days without sleep and could get “hands-on physical.”

As Brian’s baseball prospects dimmed — he struggled with how things ended in Chicago — his outbursts increased, the woman said. She said Brian was using drugs heavily; he said in court that they both were. Still, when Brian proposed in July 2017, she said yes. As a pre-wedding gift, he bought her a $5,000 Rolex.

“He promised to give me a wonderful life, and that he truly loved me and that he would take care of me financially and that he would love to have a family with me,” the woman said in court years after.

"You can’t fuck around with this drug and be a professional athlete."— Taylor, former best friend

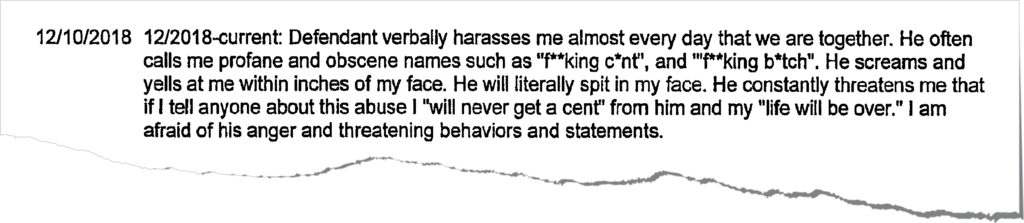

They married in November 2018. Brian went to rehab before the wedding. Overall, the woman said he went at least twice. Brian said he went only one time. By December 2019, their marriage had fallen apart. The woman obtained a protective order, accusing Brian of “terrifying and abusive behaviors.”

“He constantly threatens me that if I tell anyone about this abuse I ‘will never get a cent’ from him and my ‘life will be over,’” she wrote in her application for the protective order.

She cited several incidents she alleged happened that year, including an argument on Feb. 15, 2019. They were in the master bathroom of their Scottsdale home when it started. She wanted to know when he would start working out and stop using drugs. In response, Brian allegedly yelled at her, grabbed her by the shoulders and head-butted her.

“My nose started gushing blood and I fell to the ground,” she wrote. “He responded by telling me to get up ‘and stop being a little bitch.’”

The woman called Brian’s father, Mike, who responded, she alleged, by telling her to “take a Tylenol” and “keep this out of the media.”

A month later, on March 28, 2019, the woman said Brian was in their bedroom closet, “playing” with his gun. He put it in his mouth, she wrote. She told him she was concerned, that he was drunk. “You should be concerned,” Brian replied, according to her recollection of events. “I’m going after everybody.”

Then, in May of that year, the woman said she told Brian he was never making it back to the major leagues. He flew into a rage, she wrote, telling her to never “fucking say that again,” before spitting in her face.

The couple filed for divorce in January 2020, about a month after she sought the protective order.

Their last known interaction came in July 2021, six days before their divorce settlement was finalized. Brian and Taylor were at a basketball game — Phoenix was playing Milwaukee in Game 6 of the NBA Finals. The woman was also there with a friend. Inside the entrance of the Suns’ arena is a long bar, and she and her friend were walking past it when she noticed Taylor, according to a police report.

Then Brian appeared. The woman claimed Brian grabbed her arm and repeatedly yelled, “Oh look, it’s my fucking ex-wife!” He had a beer in his other hand, and, according to the police report, she wriggled free and didn’t see him the rest of the evening. She reported the incident to police the next day. Reached by phone, her friend confirmed the incident but declined to say anything further.

Taylor had a slightly different recollection. He remembered Brian yelled what his ex-wife said he did, but Taylor said Brian couldn’t have grabbed her arm because he was holding two beers. Instead, Taylor said, he remembers Brian putting his arm around her. Brian gave the police a third version of events, one with no mention of yelling or touching.

Authorities charged Brian with misdemeanor assault.

He was found guilty at trial.

Brian tried, and failed, to get back into baseball after the Cubs cut him in 2016.

A stint with the Arizona Diamondbacks’ Triple-A club in 2017, when he gave up 12 runs and 26 hits in 17 2/3 innings; a one-game Mexican League stint in 2019; a couple of games with the Long Island Ducks, an independent team in the Atlantic League, that same year.

In the run-up to the Mexican League game, a three-inning, five-run debacle, Brian had been in the country trying to get into playing shape.

Taylor went with him. He said Brian, fresh off his premarital rehab trip, was clean. Brian would leave in the morning to hit the gym or to throw, and when he came back later he would describe immense pain. Taylor remembers Brian saying it felt like his arm would fall off.

“All the body language, emotions, he was done,” Taylor said.

Luckily for Brian, he had made more than $20 million during his playing career. If he could not be a big league pitcher, he could at least live like one.

His houses were massive. He posted pictures of himself poolside on social media. He played lots of golf; Brian is one of the few people to ever make a hole-in-one playing right-handed and left-handed. He loved fancy cars — his favorite was his cherry red 1968 Camaro. He kept signed jerseys and baseball cards in his trunk and handed them out freely. Even people who detailed his cars got Matusz merch.

But, if anyone asked about his plans, he would tell them he was still thinking about making a comeback.

In August and September 2022, Brian served as a volunteer bullpen coach for the New Zealand Diamondblacks in the World Baseball Classic qualifiers. The Diamondblacks’ manager, Scott Campbell, played college and minor league baseball against Brian, and their older brothers were college roommates. The team gathered in Phoenix for a week of training before heading to Panama.

Brian opened his home to the other coaches, whom he did not know. He still talked about making a comeback, Scott said, but he would’ve made a good coach if he wanted. The relief pitchers got a lot from him.

They also talked about drugs. Scott’s brother-in-law had been addicted to opioids for 10 years, and Scott said Brian talked about his own use, though the extent was unclear.

“From the outside, it just looked like he was having some fun,” Scott said. “And who knows? Who really, really knows under the hood?”

It was clear to Scott that Brian was struggling with what to do next in his life. The transition from player to everyday person is difficult. Scott, who did not have nearly the professional career Brian did, struggled.

“Dealing with that grief was something I didn’t do,” Scott said. “It had an impact on my life and my marriage and my relationships.”

Eventually, Scott said, he sought counseling. As best Taylor could tell, Brian had not engaged seriously with a mental health professional. It was no secret that Brian and his father’s relationship had been built around baseball, and now that was gone. Brian would sometimes complain about his dad, but Taylor, who had been to rehab on Brian’s tab, would not push further on that, the drug use or much else.

“I knew I wasn’t going to be the one that was going to be able to have those conversations with him,” Taylor said. “He needed a professional.”

By October 2022, Brian’s family had grown concerned. The details were vague, but Taylor remembered Mike, Brian’s dad, texting him, asking “What’s Brian on?” Mike was so worried he asked Taylor to convince Brian to cancel their buddies’ trip to a reggae festival in Las Vegas planned for later that month. Taylor agreed and the trip was canceled, but he didn’t know much more about what prompted Mike’s intervention.

The next decade would be a procession of losses — his marriage, his career, his friends — until there was nothing left for Brian Matusz to lose but himself.

Brian spent much of the next few months alone in a rented home at a luxe golf community in Flagstaff, about 2 1/2 hours from Phoenix, where all of Brian’s friends and family lived. In the high country of Northern Arizona, Flagstaff got record amounts of snowfall that winter.

One weekend, at Brian’s request, Taylor went to see him. He remembers Brian largely locking himself in his bedroom for that trip. When things weren’t going well Brian had a tendency to isolate himself, which usually made things go from bad to worse, Taylor said. This time stood out. Brian was holed up in a bedroom, where Taylor believed he was getting high. When he did come out, he was muted and distant.

That same winter, Taylor’s sister and her children went to visit Brian at his invitation — the Matuszes and the Palmers were tight. Given the snow and slopes, Flagstaff made for excellent sledding. She also noticed that Brian seemed withdrawn, absent, Taylor said.

About a year later, Brian, having moved all around the Valley in a series of Airbnbs, told Taylor he was going to buy a house in Taylor’s neighborhood. Taylor remembers telling his sister, who excitedly texted Brian. What happened next was bizarre, Taylor recalled.

Brian accused Taylor’s sister of using him for money. Taylor confronted Brian, and Brian responded by blocking his number.

That was February 2024. The two men, fixtures in each other’s lives ever since they met in the schoolyard as boys — who had played Little League baseball together, who remained friends through cross-country moves, through big league fame and self-inflicted suffering — never spoke or saw one another again.

There is very little in the public realm about Brian’s life after that point.

Here is what is known.

Brian bought the house he told Taylor about: new construction with a pool, four bedrooms, three bathrooms and a kitchen that was, per the real estate listing, “darling.” The terrace, with its “awe-inspiring and coveted” view of Camelback Mountain, an ancient lump of red rock that rises out of the surrounding desert and lights up like fire in the setting sun, was the lead selling point.

His neighbors said they saw him come and go but that they did not know him well. Brian lived alone, and they could not remember a time he had people over. He drove a big, new Chevrolet truck and sports cars as well. They knew he was an athlete, a ballplayer, but that’s about it.

In the summer of 2024, a group of former teammates became concerned that Brian could not find a life after baseball. Caleb Joseph, a former Oriole and roommate of his, said it was like Brian was “stuck in a bit of a Groundhog’s Day.”

“Honestly, I don’t really know what exactly was motivating him to get out of bed,” Caleb said.

The final threads of Brian’s life unraveled in early January. His mother, Elizabeth — she goes by Liz — would later tell police Brian had been struggling. He used to have it all, and his dream had died. He would tell his mother there was nothing left for him.

At 3 a.m. on Jan. 4, Liz drove her son to an emergency room in Phoenix. The specifics are redacted in the police report, but the staff at St. Joseph’s administered Brian a dose of a drug to reverse whatever ailed him.

When Brian was released the next morning, it was recommended he seek the help of a mental health professional, so Liz drove her son straight to Banner Behavioral Health Hospital in neighboring Scottsdale, which, according to its website, treats people with “chemical dependency challenges” and psychiatric issues, among other things. The police report said he was not admitted.

"Honestly, I don't really know what exactly was motivating him to get out of bed."— Caleb Joseph, former Orioles roommate

Instead, Liz brought her son to her house in Cave Creek, a suburb north of Phoenix. Brian left that evening. Liz wanted to check-in on her son the following day, but the staff at St. Joseph’s lost his phone, so she made the roughly 40-minute drive to his house.

When Liz arrived in Phoenix at 2 p.m., she went to Brian’s front door. No answer. She went around the side and crawled through a bathroom window on the ground floor. She found Brian lying on a couch upstairs. There was a white substance in his mouth. He was cold to the touch.

The officer found a straw, a lighter and a piece of unburnt foil next to his body. The autopsy report is sealed at his family’s request.

On a night in early spring, as the sun set and the desert’s warmth faded, Brian’s house sat empty. The blinds were drawn, and fake flowers filled the window boxes. A light next to the front door was on. It had burned all day.

Brian’s family had come by recently, the neighbor across the street said. They were moving furniture and doing something with the cars. The neighbor talked to Liz, who said she was worried about reporters digging around in her son’s past.

There were things the family wanted to keep private. They have lost a son and a brother, and people who know them said the family would like to remember the good days.

The Matuszes are devout Catholics, and Brian’s funeral Mass was held at St. Thomas More Catholic Church. Hundreds attended — teammates, friends, family. People who‘d seen him pitch, who‘d known the all-American kid.

A parish receptionist said the funeral had three readings. Two were traditional passages from the Gospel of John, ones that tell Christians God gave his son for them and, if they believe in him, they will get to heaven.

The other came from “The Wisdom of Solomon.” It read, in part: “But the souls of the righteous are in the hand of God and no torment will ever touch them. In the eyes of the foolish they seemed to have died and their departure was thought to be an affliction and their going from us to be their destruction; but they are at peace.”

Brian was laid to rest in the Holy Redeemer Catholic Cemetery, 15 minutes down the road from his parents’ house. The cemetery, neat and quiet with shade trees and manicured grass, is an oasis in the middle of the desert. In late February, a piece of painter’s tape bearing his name, not unlike what big league teams use on a newcomer’s locker, marked the red granite panel where his ashes lay. The panel faces to the southwest, just like the pitcher’s mound in Oriole Park.

Banner reporter Darreonna Davis contributed to this article.

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.