Even as Baltimore celebrated Cal Ripken Jr.’s ascent to his iron throne, a more clandestine sporting drama — with more seismic implications for the city — unfolded.

Sept. 6, 1995, baseball fans everywhere turned their eyes to Camden Yards to watch Ripken play his 2,131st straight game. John Moag and Al Lerner were among the powerful people at the ballpark that day, and amid all the hoopla, they found an out-of-the-way corner.

Moag, a precocious Washington lobbyist entering his seventh month as chairman of the Maryland Stadium Authority, told Lerner a deal was within reach.

OK, said the cigar-puffing credit card purveyor who’d been part of Baltimore’s failed effort to obtain an NFL expansion franchise. It was time for Moag to meet face to face with Lerner’s partner, Art Modell.

On Sunday, the Ravens will celebrate their 30th season in Baltimore before and during their home opener against the Cleveland Browns. It’s an occasion that would not be possible had Moag not coaxed a reluctant, distraught Modell away from Cleveland three decades ago this fall.

It’s a strange thought for older football fans in this town, but the Ravens have now been Baltimore’s team nearly as long as the Colts were before they fled to Indianapolis.

Read More

Several generations have grown up knowing allegiance to no previous team. As such, it’s easy to forget the Ravens were born of desperation — from a city that could no longer stomach living without the NFL and an owner convinced he’d never get the new stadium he needed to thrive in Cleveland.

Modell wept before he signed the agreement to move his team, on his business partner’s private jet parked on a back lot at Baltimore-Washington International Airport.

As the news leaked over the next week, not all Baltimoreans rejoiced unreservedly. Yes, they had waited almost a dozen years for this moment, but they were doing to another proud city what had been done to them when their team vanished on a fleet of Mayflower trucks the night of March 28, 1984.

Who could have guessed then that a franchise spawned from two cities’ pain would become one of the most stable and respected in America’s most popular sport?

Moag could not know that Modell would hand football operations to one of the greatest general managers in league history, Ozzie Newsome, who would immediately draft a pair of Hall of Fame talents with his first two picks for the Ravens. He could not know that Modell’s successor, an Anne Arundel County billionaire named Steve Bisciotti, would bolster the Ravens’ finances while maintaining his predecessor’s commitment to winning without meddling. He could not know that a franchise without any Super Bowls to its name would win two in the next 17 years.

But he did know he wanted Modell more than the other owners who might take the stadium deal he was dangling.

“The No. 1 reason for that was that he wanted to win football games really, really badly,” Moag said. “I couldn’t say that about the others.”

Moag had grown up in the shadow of Memorial Stadium, parking cars for $5 a pop on Colts game days. The pain of losing the team was personal to him. He can still feel the fabric of his wife’s nightgown the morning he flipped on the news to watch the Mayflower trucks rumble out of town. He can still picture all the cars with their lights on as if the whole city was mourning a departed loved one.

For 11 years, he followed, as a fan, the city’s faltering quest to regain a team. After the league chose Jacksonville and Charlotte as expansion destinations in 1993, he assumed the dream was dead, that, in his words, NFL officials viewed Baltimore and St. Louis as “old, decrepit cities.”

NFL Commissioner Paul Tagliabue seemed to confirm as much when he said Baltimore would be better off building a museum with the state funds earmarked for a new football stadium.

“The only way we were going to get a team was to steal one. And I was going to be the robber.”

John Moag, former Maryland Stadium Authority chairman

By early 1995, Maryland Gov. Parris N. Glendening had decided it was time to stop playing nice. He needed a dealmaker who’d find a team by any means necessary. He tabbed Moag to replace Herbert J. Belgrad atop the stadium authority and gave him until the end of the year. Get it done, or the $200 million for a stadium would go to other projects.

“I came into the job like everyone else, thinking, ‘We’re never going to get a team,’” Moag recalled last week, speaking to a crowd of Ravens fans at an event organized by Hunt Valley-based Harvest Investments.

He changed his tune after speaking with Carolina Panthers owner and former Colt Jerry Richardson, along with a few other power brokers. No, Baltimore wouldn’t get an expansion team, but that $200 million for a new stadium was quite the hook for owners dissatisfied with their situations.

“The only way we were going to get a team was to steal one,” Moag said. “And I was going to be the robber.”

Potential targets included Mike Brown in Cincinnati, Bill Bidwill in Arizona, Bud Adams in Houston and Malcolm Glazer in Tampa Bay, all of whom Moag met in secret.

Still, he couldn’t stop looking at Cleveland, where Modell was disgruntled with his dilapidated stadium, especially after public money flowed into a new baseball park, a new basketball arena and the Rock ’n’ Roll Hall of Fame. Modell felt local officials were dragging their feet on promises to him. Even so, he was the one owner who would not talk to Moag.

Meanwhile, the stadium authority chairman had to avoid (not so) friendly fire from Orioles owner Peter Angelos, who told him, “You stay the f--- out of football. That’s for me to do,” poking him in the chest to emphasize the point.

Moag continued his lonely quest, finally discovering that Lerner was his way in on the Browns. In July, the MBNA chairman, who owned a small stake in the team, flew to Baltimore and invited Moag for a sit-down aboard his private jet. Lerner knew the details of the potential stadium deal from his work with the 1993 expansion push. He seemed interested.

Moag left the meeting so charged up that he stopped by Glendening’s office on his way to a family beach week in Delaware to tell the governor he thought Baltimore would land the Browns.

He met with Lerner twice more, including at Ripken’s historic game. Less than two weeks after that, Moag and his top two stadium authority lieutenants made their pilgrimage to New York, armed with $800 worth of Davidoff cigars for Lerner and Modell’s son, David. In Lerner’s Manhattan office, framed by a panoramic view of Central Park, the Baltimore contingent finally met Art Modell in the flesh.

“It was extremely emotional,” Moag recalled. “He was in tears, and he said, ‘You don’t understand. This is a very big deal for me and my family. We’re going to have to pack up and leave Cleveland.”

Moag assured him that Baltimore “is going to be good to you.”

They spent 45 minutes going back and forth. “I could tell when I left that this deal was going to get done,” Moag said.

A few weeks later, Modell told Kevin Byrne, the Browns’ public relations director, that he was about to fly to Baltimore with the expectation that he’d sign a deal to move the team. Byrne, who’d go on to work for the Ravens until he retired in 2020, was gobsmacked. Even at that late hour, he sensed Modell was waiting for some city or state official to “come charging in on a white horse” with a new stadium deal.

It never happened.

The sides made it official on Oct. 27, again aboard Lerner’s jet. Moag’s wife, Peggy, packed his green Lexus with brown and orange balloons that morning. David Modell spilled coffee on Glendening’s shoes. The governor served as witness while Art Modell and Moag signed the documents.

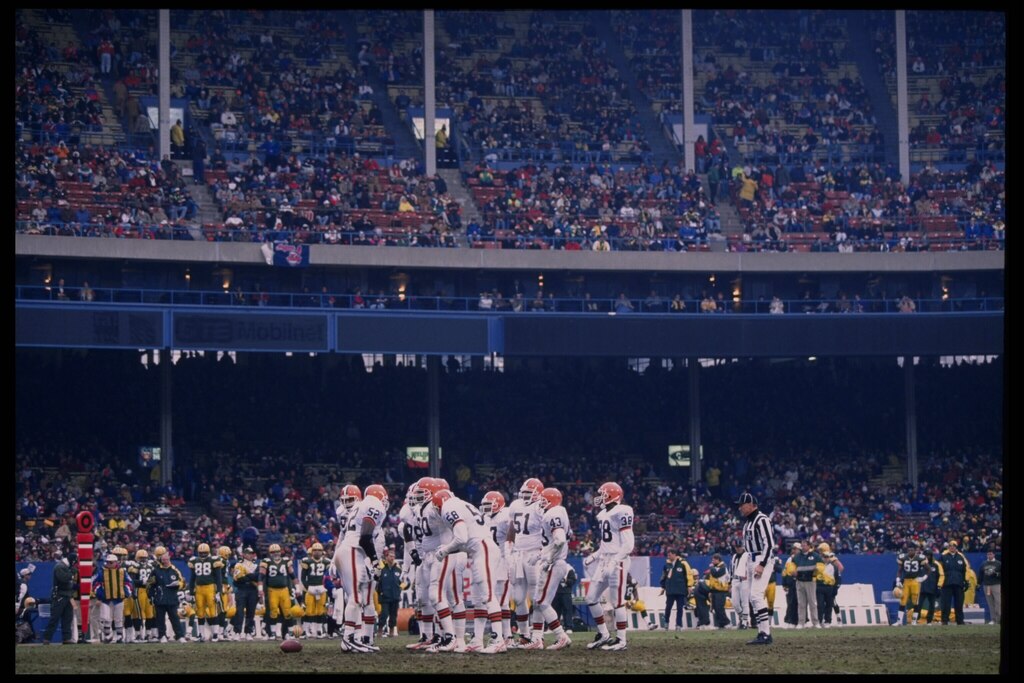

Their plan was to keep the move secret for two months to avoid destroying the Browns’ season, which had started promisingly under coach Bill Belichick. That wasn’t in the cards. By the time the Browns took their home field to play the Houston Oilers on Nov. 5, everyone in Cleveland knew the announcement was coming the next day. Modell had never missed a home game, but he watched from Florida on the advice of security guards.

Byrne’s private line in the press box rang during the game. “How is it there?” Modell asked.

“It’s awful,” Byrne replied. “Your body has been hung. You’ve been in an electric chair. They’ve burned you.”

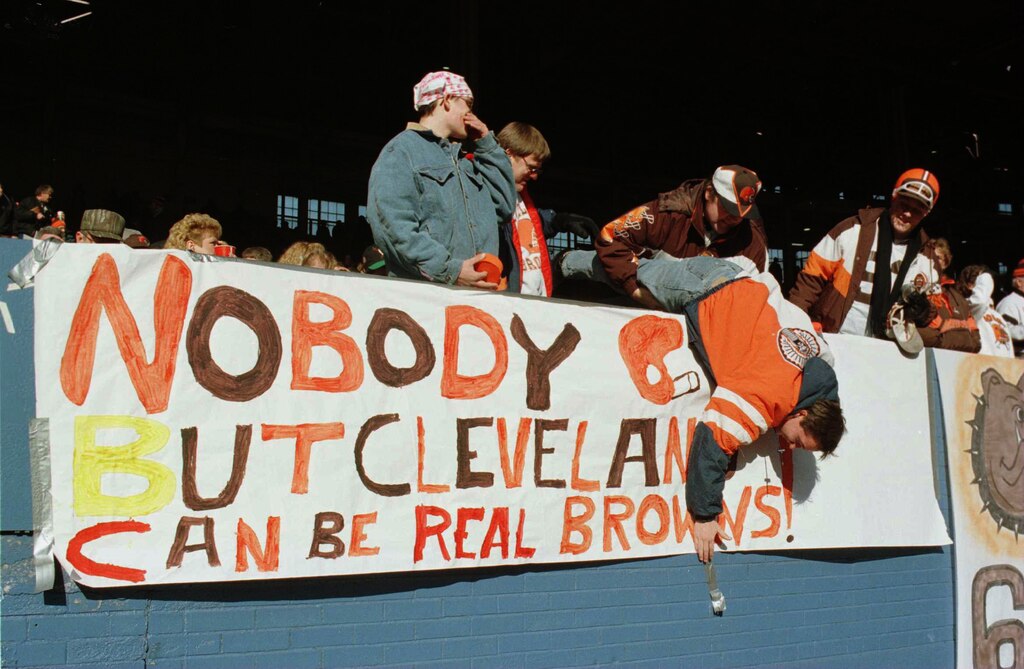

One fan held a sign above the empty owners box that read, “Jump Art. Jump!”

Modell called Byrne back about 30 minutes later and suggested that team officials dress a dummy in the owner’s trademark camel hair coat and send it leaping from the owner’s box to the lower concourse.

“I don’t think we’re ready for that,” Byrne replied cautiously.

“Kid, I’m just trying to put a smile on your face,” Modell said.

Cleveland Municipal Stadium was silent as a tomb. The crowd of 57,881 began dissipating early as the Browns lost meekly, 37-10.

“The Browns fans were hurt,” said kicker Matt Stover, who was in his fifth season in Cleveland and would go on to become an institution in Baltimore. “They had been such loyal fans for so long that they couldn’t believe their team was being taken. The city was not doing the necessary things to help Art Modell be competitive. … But I felt horrible for the people. I had bought a house in the community. I had just signed a new contract.”

That day, Cleveland Mayor Michael White flew to New York to petition Tagliabue and then to Baltimore, where he held a news conference, proclaiming Cleveland would fight to keep its team.

The next afternoon, Glendening stepped up to a microphone in the parking lot outside Camden Yards and shouted: “This is a great day for Baltimore, this is a great day for the state of Maryland, and, personally, this is a great day to be governor.”

Modell made no effort to hide the bittersweetness of his decision, saying he “had no choice” but that “I leave my home of 35 years and a good part of my heart there.”

Sports Illustrated rendered its verdict that week, depicting Modell sucker punching a dog in a Browns helmet on its cover.

The team’s season circled the drain, even as whirlwind preparations began for the move to Baltimore.

The Browns managed to win their last home game, 26-10 over the Bengals. Afterward, players made it clear they didn’t like what was happening.

“I think we’re going to reflect back on it after the season and there’s going to be a hole inside of us,” quarterback Vinny Testaverde told The Cleveland Plain Dealer. “Something’s going to be missing, and it’s that we’re not going to be playing here.”

The deal was not done with the announcement. A super majority of NFL owners had to approve it three months later, and several, including Bob Kraft of the Patriots and Ralph Wilson of the Bills, said publicly they would not support Modell.

Moag worried the entire time, wondering if Modell’s resolve would crumble in the face of the terrible vitriol thrown his way or if the NFL would block the move by promising that its next expansion team would go to Baltimore if Maryland officials built that $200 million stadium on spec.

But Modell held firm and the move was sealed with a promise that Cleveland would get an expansion team by 1999, with the Browns’ name, colors and history attached.

The former Browns had no name when they lined up for their first practices at their new home. They wore white uniforms and black helmets, leading some players to compare themselves to the prison team in Burt Reynolds’ film “The Longest Yard.”

But by the time the newly christened Ravens hosted the Oakland Raiders at Memorial Stadium on Sept. 1, 1996, they sensed how badly Baltimore wanted them.

Byrne knew it after he took a handful of players around their new community to help spur ticket sales in the spring. “Everywhere we went, it was electric,” he remembered. “The reception was just top of the line. It was just a relief.”

Browns officials understood how important it would be to connect with the old Colts who remained heroes in the city. The greatest of them all, Johnny Unitas, held out the longest. He asked Byrne to set up a meeting with Modell.

“John wanted to make sure Art wasn’t [former Colts owner Bob] Irsay,” Byrne said.

Modell charmed Unitas with his passion for football history. At the end of lunch in the owner’s office, the Hall of Fame quarterback told Modell the NFL wasn’t doing enough to support retired players.

“You have a voice now,” Modell told him, promising to speak out in league circles.

An armada of former Colts, with Unitas at the front, greeted the Ravens for their Memorial Stadium debut. Belichick was gone, replaced by another former Colt, Ted Marchibroda.

“Everything was going 100 miles per hour; it was almost too much to take in,” said longtime Baltimore broadcaster Bruce Cunningham, who called the first game for radio with Scott Garceau and former Colt Tom Matte. “They moved here in March or April, and the lights were on in September. That’s remarkable.”

Ravens center Steve Everitt wore a Browns bandanna in solidarity with Cleveland, but most of the carryovers adapted.

“We were like an abused, adopted stepchild,” Stover said. “Baltimore, I’ll say this, they did an amazing job of loving us, accepting us as theirs. They were long overdue, because their kid had gotten ripped away from them. Even the band stayed together.”

The Ravens won just 16 games over their first three seasons, leading some fans to grumble that perhaps Moag had picked the wrong team. We know what happened from there. They’ve made the playoffs 16 times in the last 25 seasons and drafted some of the most beloved athletes in the city’s history, from Jonathan Ogden to Ray Lewis to Ed Reed to Joe Flacco (visiting with the Browns this weekend) to Lamar Jackson.

Browns fans did not have to wait nearly as long — three empty seasons — as their Baltimore counterparts to greet another team. That doesn’t mean all wounds are healed.

Just like the name Irsay in Baltimore, Modell will probably always be a dirty word in Cleveland, never mind the family’s contributions to that city’s medical and cultural institutions.

This week, several Cleveland sports media stalwarts have said it’s insensitive for the Ravens to celebrate their 30th season when they’re playing the Browns.

As for Moag, he flew on the team plane to Tampa for the Ravens’ Super Bowl matchup with the New York Giants. After an all-nighter celebrating the victory that could not have happened without his deal, he ran into defensive tackle Tony Siragusa, who hoisted him like a rag doll.

“Thank you,” the boisterous “Goose” said, “for bringing me to Baltimore.”

Comments

Welcome to The Banner's subscriber-only commenting community. Please review our community guidelines.